The virtue of ancient carbon through empirical analysis.

Conventional wisdom says that fossil fuels are an unsustainable form of energy that is killing the planet. We hear proclamations about the danger of fossil fuels (and by extension, climate change) everywhere in popular culture, but it’s seldom that the question of why we use fossil fuels to begin with is asked.

Recently proposed legislation like Alexandria Ocasio Cortez’s Green New Deal has advanced and accelerated the popular notion that the oil and gas industry’s days are numbered. Although that proposal died unceremoniously in congress with not even a single vote, the core idea in the proposal is a popular one: that fossil fuel use should be halted in the United States.

The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels goes a step further than comparing the costs and benefits of fossil fuel use, to make an argument for why fossil fuels aren’t just necessary for modern civilization to function: it is the most moral choice for human progress.

If you’re like most people you might find this assertion to be far fetched at best, or absurd at worst. It was the contentious claim made in the title of this book which drew me to it. I had to know what the moral argument for fossil fuels could possibly be. It turns out that it’s a convincing one.

That is, if you consider things like measurably improving living standards and life expectancy and reducing disease and infant mortality (among both the rich and poor around the world) to be a moral good.

The Importance of Energy

There are over 7 billion people on earth who rely on cheap, plentiful, and reliable energy to flourish. Almost 3 billion of those have virtually no energy by our standards, which means the world needs a lot more energy.

Currently, about 87% of all global energy around the world comes from fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. Think of the energy industry as the industry which powers every other industry, and you begin to get an idea of how critical it is to human progress. Restricting or eliminating fossil fuel use would have disastrous effects on virtually every industry which we consider important to our daily lives: aerospace and automotive, healthcare, manufacturing, agriculture, and information technology, to name just a few. Oil in particular is everywhere, in places you wouldn’t even imagine. To give an example:

Chemists can “crack”—break down—the molecules in a barrel of oil into small parts, and then reassemble them into an unbelievable variety of polymers, including modern plastics. While you think of oil in your car as in the gas tank, in fact there is more oil in the materials in the car than in the gas tank. The rubber tires are made of oil, the paint and waterproofing are made of oil, the plastic, dent-resistant bumper is made of oil, the stuffing inside the seats is made of oil, and in most cars, the entire interior is one form of oil fabric or synthetic material or another—because oil is such a cheap and effective way to make things.

Renewable Alternatives

Much is made of solar power as an alternative to fossil fuels in particular, and it’s easy to understand why: if humanity could meet our energy requirements from just the sun, it would solve a lot of problems. Problems like emissions, environmental degradation from mining and drilling, and oil spills. Unfortunately we are far from that outcome, as solar power in the United States currently generates just over 1% of the energy we use.

Solar power presently has two major problems which limit its applicability: the diluteness problem and the intermittency problem. The former is that the sun doesn’t deliver concentrated energy, which means you need a lot of materials per unit of energy produced. You need a large volume of panels and materials like purified silicon, phosphorus, boron, and compounds like titanium dioxide and cadmium telluride. The intermittency problem is that the sun isn’t always shining in all places – it’s not a plentiful resource unless you’re somewhere like Arizona. But if you’re in Nebraska, your energy cannot come from solar cells in Arizona because we don’t have efficient means to store and move that energy over long distances. What this means is that solar power is only economically viable if you’re in a region conducive to it – and as it turns out, the same can be said for wind, hydroelectric, and most other forms of renewable energy which rely on regional geographic features like the shining sun, blowing wind, or rivers.

What would happen if the US government were to massively subsidize solar power as an energy source? We can look at Germany which has done exactly that. Germany is the world leader in solar production after investing tens of billions, but it still generates only 4% of its energy needs from solar power. In the time that Germany has has invested in this infrastructure, it has not only not banned its use of fossil fuels, but its use of them has increased. Observers claim that Germany is addicted to coal but it’s not coal they’re addicted to necessarily; they are eager to switch to a similarly cheap, plentiful, and reliable energy sources, but those aren’t easy to find.

With that in mind, Germany has plans to ban coal, which presently generates over 40% of its electricity, by the year 2038. What will replace it? Maybe natural gas, but Germany is already the largest importer of natural gas in the world – in 2016 it imported a record-high 48.6 billion cubic meters of gas from Gazprom, the state-owned Russian oil company. Ditching the benefits of fossil fuel production is easier said than done.

Inaccurate Forecasts

We’re used to hearing about how we’re facing a cataclysmic event due to global warming, or climate change. It’s easy to see why predictions of future catastrophe hold so much power over our collective attention: we’re naturally fearful of threats, as far away and shadowy as they may be. We’re not as good at determining which threats are real, or at revising our outlook based on inaccurate predictions of the past.

“If I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.”

American biologist Paul Erlich in the 1970’s

Since the 1970’s we’ve been hearing alarmist predictions about global catastrophe related to fossil fuel use or climate change (as the author Alex Epstein explains, the two are linked, as CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use is inarguably linked to the warming atmosphere).

“Carbon-dioxide climate-induced famines could kill as many as a billion people before the year 2020.”

University of California physicist John Holdren in 1986

In 1989, the UN claimed that by the year 2000 coasts would be flooded, island chains would disappear, and the world would be turned into a mass of “eco-refugees.” “Entire nations could be wiped off the face of the earth by rising sea levels if global warming is not reversed by the year 2000.”

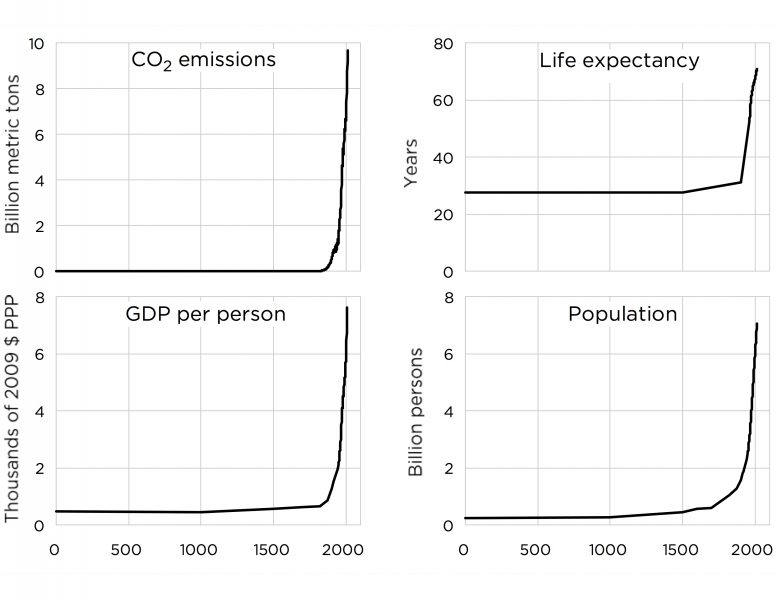

Instead of halting progress by eliminating fossil fuel use, humanity has gone the other direction: fossil fuel use sharply increased, and rather than resulting in the kind of doomsday scenario predicted by “experts”, virtually every objective indicator of human progress has seen hockey stick growth. Not only were the predictions inaccurate, but the exact opposite happened. Instead of long-term catastrophe, we’ve experienced dramatic improvement in nearly ever facet of life, including environmental quality. One common element of alarmist predictions is that they focus on the risks of a technology while not acknowledging the benefits. The moral position for fossil fuels hinges upon empirical analysis of the material ways that energy derived from fossil fuels improves human life.

Scarcity & Depletion

It’s true that coal, oil, and natural gas are limited resources. They aren’t taken from nature, but created from nature. They are high-concentrations of ancient dead plants, compressed over millions of years, made up of hydrogen and carbon atoms connected by chemical bonds.

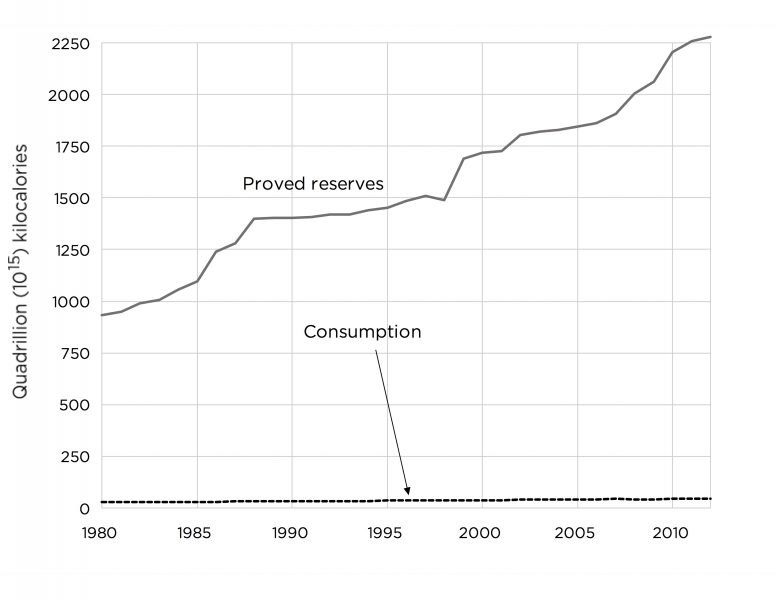

You’ve probably heard predictions about when humanity would run out of oil or coal, but these are misleading because we are always creating and improving technology to find new and larger deposits. Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a technology used to get natural gas out of shale, and has turned previously known but unusable deposits into cheap, accessible natural gas. As a result, proven reserves of natural gas have increased 46% in the United States since 2005 alone and the US became a net exporter of oil for the first time in decades.

There are estimated to be far more natural gas reserves across the planet, in difficult to reach places. One of those places is at the bottom of the ocean, where natural gas deposits are in a frozen form called methane hydrates. Judging only by the deposits we’re already aware of, humanity has enough natural gas to last for centuries.

In 1992 Al Gore argued that the combustion engine, which has allowed us to go anywhere, anytime should be outlawed in twenty five years time (i.e. 2017). The biggest threat to the cheap and abundant energy which powers modern civilization is not scarcity – it is legislation. Fossil fuel use will be banned or technologically obsolete long before we ever run out.

Global Warming

As you might expect, there is a chapter devoted to this topic in the book. One of the first reactions to the central argument presented in this book is: “How can fossil fuel use be moral if it contributes to global warming, which threatens the planet?”

The subject of global warming is a large and complex one, but the simple responses to this question presented in the book are:

- In order to judge the merits of fossil fuel use we must logically evaluate the benefits and costs of its use. If fossil fuel use were stopped today, the world would lose over 80% of its current energy. This would dramatically affect our ability to build and maintain hospitals, grow food, manufacture pharmaceuticals, drive cars and fly airplanes, and power the countless other necessities of daily modern life.

- What amount of global warming is natural, and would occur if humans didn’t produce CO2? We know that earth has gone through heating and cooling periods for billions of years, long before the industrial revolution. What if humanity were to cripple itself by halting the use of fossil fuels but it didn’t stop the rise in temperature? Exactly 1,000 years ago, earth went through a Medieval Warm Period where temperatures were warmer for 300 years. After that was the Little Ice Age, which lasted until the end of the 19th century. No one knows exactly what amount of modern warming is due to human intervention.

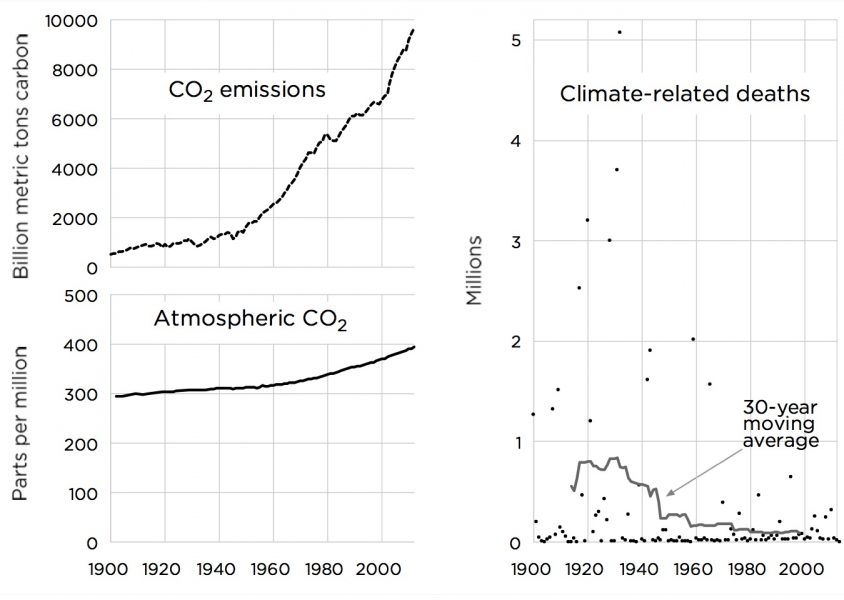

Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, CO2 in the atmosphere has gone from just under 0.03% (270 parts per million, or ppm), to today around 0.04% (396 ppm). Over that same time period, temperatures have gone up less than one degree Celsius, a rate of increase that has occurred at many points in history. There is a seldom-discussed benefit to rising CO2 levels as well: more rapid vegetative growth, due to CO2 being plant food (ironic since greenhouses are generally regarded as nice things to have). One of the discoverers of the greenhouse effect, Svante Arrhenius, regarded CO2 emissions as a positive phenomenon when he said this in 1896:

“By the influence of the increasing percentage of carbonic acid in the atmosphere, we may hope to enjoy ages with more equable and better climates, especially as regards the colder regions of the earth, ages when the earth will bring forth much more abundant crops than at present, for the benefit of rapidly propagating mankind.”

Our climate is naturally dangerous. Extreme cold, extreme heat, storms, wildfires, floods, and droughts have led to human deaths throughout history. Fortunately for us, over the last century climate related deaths are down 98%, including the undeveloped world. This isn’t because these events have stopped happening, but rather because we now command the energy required to do things like build safer structures and move people away from danger zones in times of need.

Morality

Whether you see fossil fuels as a moral good or evil depends largely on your view of humanity’s relationship with the earth. Believe it or not, many people look forward to the extinction of the human race. To antihumanists, humanity is the problem. Prince Philip, former head of the World Wildlife Fund, has said: “In the event that I am reincarnated, I would like to return as a deadly virus, in order to contribute something to solve overpopulation.” And he’s not alone – many people believe that advancing human prosperity is immoral.

If you’re a humanist on the other hand, you might consider improving the lives of humans all across the planet to be the moral choice. We don’t want to “save the planet” from human beings; we want to improve the planet for human beings.

- View all of my highlights from The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels

- The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels on Amazon

The post The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels appeared first on Just Charlie.